11 - Life Among the Dead at Green-Wood Cemetery [Wild Talk Short]

“I don’t think it’s hokey to think of the cemetery as a place where you can think about life. And I think that’s the whole point. It was conceived that way, to have these large living organisms be in a place in which the dead were buried, it’s showing, not in a subtle way, the continuity of life.”

Green-Wood Cemetery, in the middle of Brooklyn, feels unexpectedly wild. The 478 acres are alive with big old trees, flowers, bees, fungus, birds, wild and feral animals. Yes, it's also full of dead people — the “permanent residents” of Green-Wood, as they refer to them, comprise a Who’s Who of 19th century New York: famous actresses and Civil War generals, industrialists, businessmen, developers. There's Boss Tweed, there's Samuel Morris, inventor of the Morse code. But a visit to Green-Wood makes it clear that this cemetery is for the living. It's not just a burial ground. It's a breeding ground. A place of birth and renewal and life and excitement.

Join Wild Talk producer Matt Dellinger as he strolls among the graves with Joseph Charap, Green-Wood’s Director of Horticulture, and Sara Evans, the Manager of Horticulture Operations and Projects. The interviews were recorded last Spring, in April 2021, as vaccinations were first made widely available, the first time it seemed possible to imagine the worst of the coronavirus pandemic was behind us.

Transcript

Matt:

Yeah, we're sort of looking out here, we're up on a hill and we see the statue of Liberty. We see Ikea.

Sara:

We see the Brooklyn Queens expressway.

Harry:

And we have this lore about the cemetery where they say that the founders of the cemetery, Henry Purpon and it's designer, David Bates Douglas came here and thought that it was close enough from a day trip from Manhattan but far enough away that it would never get developed, and we see that the con Edison plant on one side and the Jackie Gleason bus terminal and all this urban sprawl in front of us now. It is developed, but the landscape is maintained and because it's a landscape that's maintained in perpetuity, as our responsibility to our lot owners, it also gives us the opportunity to say, what are the best practices to make sure the landscape is around in the future? What do we need to change and how do we need to adapt what we're doing in order to make and preserve the landscape moving forward.

People:

Welcome to Wild Talk.

Emily:

Let's head outside.

Matt:

Greenwood cemetery is an oddly wild place. It's in the middle of Brooklyn, kind of near Sunset Park, south of Prospect Park. 478 acres that feels unexpectedly wild, big old trees, bees, fungus, birds, flowers. But of course it's also full of dead people. I've been going to Greenwood cemetery for years now. I don't know anyone there. I mean, I didn't know anyone before they died, but I've gotten to know some of the dead people there. I'm, I'm writing a book about a civil war regimen from Brooklyn, and many of the soldiers and officers are buried there. And I've even gotten to do some zoom lectures with the historian Jeff Richmond. But believe me, when I tell you that Greenwood cemetery and their permanent resides as they call them, it's a who's who of the 19th century. You've got famous actresses and Civil War generals, industrialists, businessmen, early developers of Brooklyn, there's Boss Tweed, there's Samuel Morse inventor of the Morse code. In fact, Jay Erickson, the host of this podcast, and I once drank hard cider from apples grown on the grave of Samuel Morse. And that tells you a little bit about Greenwood is today. It's not just a burial ground, it's a breeding ground, it's a place of birth and renewal and life and full of excitement.

Harry:

Rural cemeteries. We often discuss this as the sort of the first publicly accessible green spaces, they freed it. All the Botanic gardens, all the public parks and they offered city dwellers an opportunity to experience nature within an urban environment, fresh air, and being around trees. My name is Joe, and I'm the director of horticulture.

Matt:

And you grew up in Manhattan, which is, I guess, a counterintuitive place for someone, a horticulturalist, maybe one might think.

Harry:

Yeah, I grew up with a healthy fear of trees, I think. And I graduated from college and I got a master's in literature at Brooklyn College, and I was doing a post back to go to medical school. And I began working at a research lab that specialized in researching paternal age related schizophrenia, so of the schizophrenia from the age of the father at the time of conception. While I was doing that, which was pretty emotionally taxing work, I would help a friend who had a gardening business do plant installs. That led to me building the site, which I got married to my wife in Connecticut, and from there I just had the bug. I wanted to learn a lot about plants and then met a woman who was the vice president of Glasshouses and Conservatory at the New York Botanical Garden at a dinner. I just happened to sit next to her, and I asked her where she trained. She referred me to this school of professional horticulture at the New York Botanical Garden, which she had attended. And so a month later I had applied and this has been my track ever since.

Matt:

Amazing. And do you still live in Manhattan?

Harry:

We actually live here in the cemetery. my, my family and I. I'm serious. Yeah. Wait, there's a house over on Fort Hamilton Parkway, the Gothic structure that I live in.

Matt:

Are you kidding?

Harry:

No.

Matt:

That comes with a job?

Harry:

It, it comes, no, I, I just, it was offered to me and my family a few years ago and it was renovated and we moved in.

Matt:

That is insane.

Harry:

Yeah. We're still very fortunate. So I live there with my wife and two children.

Matt:

You live in a cemetery? The kids are growing up in a, this is going to be a children's book, obviously.

Harry:

My son is three and a half and my daughter is eight months.

Matt:

So they're really growing up in a cemetery?

Sara:

Yeah, with a healthy sense of mortality from a very early age.

Matt:

Does that hover over your work life? I mean, do you think about death regularly now or is it all just sort of backdrop?

Harry:

I mean, I don't think about death anymore than I used to think about it. I think what it, what working in a cemetery has really hit home is that death is inescapable from life. And that, you know, we plant trees and we plant living organisms in the ground, they grow, some of them die and people live and die and it's a part of life. It's just made it more matter of fact.

Sara:

When you're out in the field doing field work, there are like over, I think, like 400,000 monuments on this ground. So you're constantly coming upon like little treasures, like a headstone that you've never seen, you're coming across a name or like there will be something inscribed on the epitaph. And you know, this job is really cool in that we are able to preserve memories of, or, you know, just like the names of people who otherwise might have been forgotten.

Hi, my name is Sarah Evans and I'm the manager of horticulture, operations and projects at Greenwood. So I was born and raised in Maryland. And then I moved up here when I transferred from American University down in Washington, DC and completed my undergrad at Brooklyn College. My major is urban sustainability concentrations in environmental science and sociology. Part of my job is to oversee a lot of the research initiatives and support them. And upcoming, I will be supervising and Greenwood will be hosting research into feral cats of New York city. This will be done by a student from Columbia university. And essentially it's going to be a tracking. It's going to be tracking research where they're going to look at sort of just like contract tracing of where these cats are going. So where they're going, wow. Sort of what resources they pool around. We're also going to be collaring other wildlife. So like some of our groundhogs, our skunks, our raccoons that are here to also when they are interacting with one another. The feral cats in New York City are just booming.

Matt:

That's it? And, and so they come through the cemetery or that's just, you're supporting them?

Sara:

So no, there's a colony of cats that lives just behind our service yard. So those are the cats that are primarily trapped, released, or rather returned, and studied.

Matt:

Okay. Like DNA?

Sara:

Where they go there will be samples taken, yeah. So blood, stool, urine, saliva, any parasites will be removed from them, they're going to be vaccinated. Yeah.

Harry:

There's another pretty notable feral population at Greenwood, they're kind of hard to miss. When you come in the main entrance of Greenwood Cemetery, there are these big Gothic, Gothic revival, arches designed by Richard Upjohn and they're built in 1861 of brownstone. They've got biblical scenes tucked throughout the arches, and tucked throughout the biblical scenes, and the Gothic details up high are nests of monk parrots. According to local birder Steve Baldwin, they came from Argentina in the 1950s. It was sort of a craze back then to bring parrots as pets and they got loose from a ship or from people's homes and it became a real problem in New York City. And the city actually sent out death squads, apparently, to kill all the feral parrots in the city, and this group escaped and took up residents at Greenwood Cemetery. And you can hear them squawking constantly, almost year round. They're loud and it's exotic and haunting. They're an invasive species, of course, but aren't we all?

So these, sort of modest looking trees are..

Sara:

They haven't leafed out yet. They're semi-evergreen.

Harry:

Yeah, so these are Southern Live Oaks. They were collected as part of a seed collecting trip by Arnold Arboretum and Morris Arboretum. Michael Dosmann and this was from the northernmost seed population near the University of Richmond's cafeteria. This tree was growing there only, they took seeds from it and the US Arboretum propagated them and then gave us 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 of them. And we planted them when they were about this big and we didn't think they were going to make it through the winter. And this is their fourth year now.

Matt:

Is that like a quarter around or a nickel around, what do you got there?

Harry:

Oh, sorry, yeah.

Sara:

They were like this tall.

Harry:

So like three feet tall.

Sara:

Yeah, they were saplings, if you will.

Harry:

Yeah, and now they're over eight feet tall. Trees that were considered marginally hearty in this zone now are thriving here and suggest not only something about assisted species migration, but also about the appropriateness of certain trees, the utility of Southern species in New York or in Northern climates, which are getting warmer. So are these the trees that are going to be the Oaks that we have around the city in the future? Who knows, but it's, you know, a landscape such as this, with this much size gives us the opportunity to experiment and try these different things that we've been trying because we have this resource and we feel like doing stuff like this is part of our responsibility.

Matt:

So do you suspect that the trees would not have survived 20 years ago?

Harry:

No.

Sara:

According to the US/GS hardiness zones. Yeah, no.

Harry:

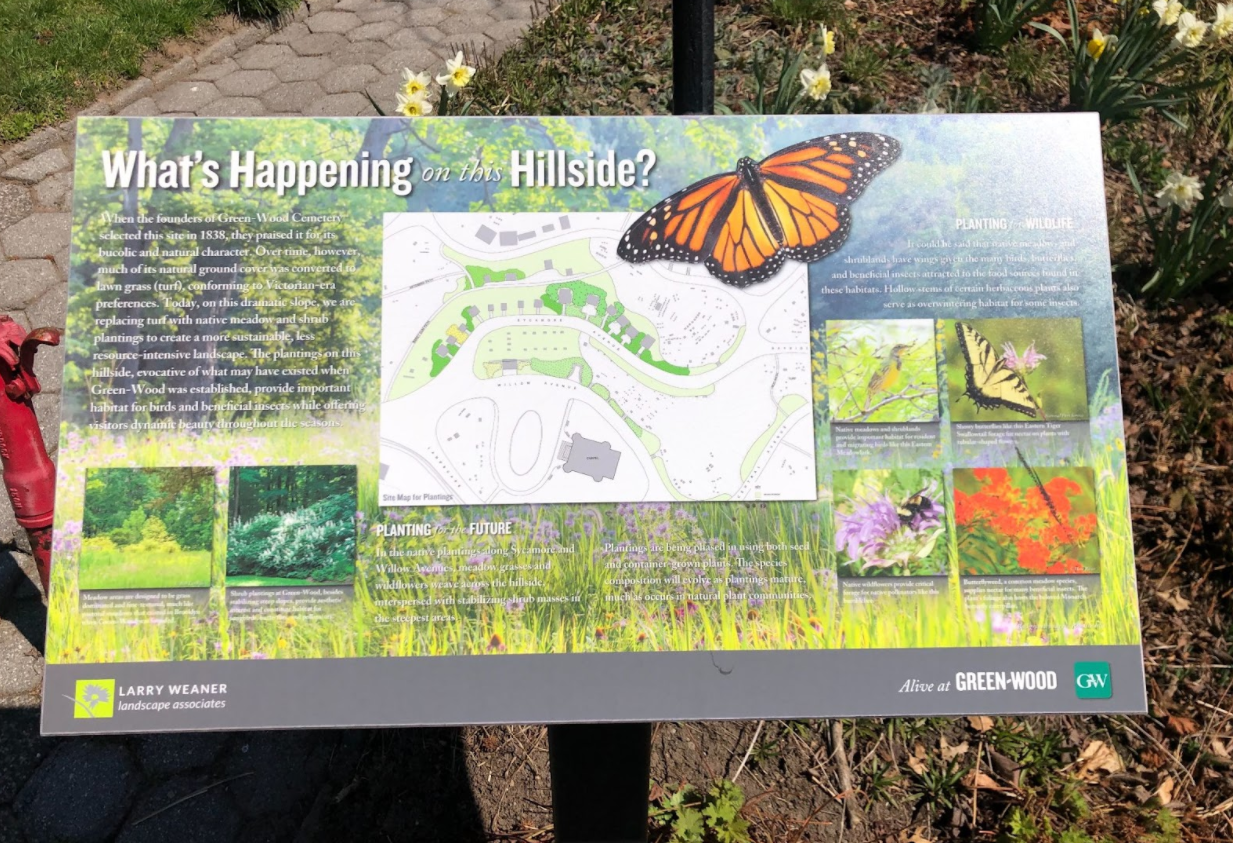

I don't think so. And we use this planting with an interpretive panel here, which is part of an interpretive program that we call "The Live at Greenwood". Which, also, we have a mobile app that's in English and Spanish that talks about all of these things as well. But we created this (inaudible) here, which is 10 feet tall quarter ton steel (inaudible) with a plaque in front that says "Planting for the future", and it describes global warming. And doesn't sort of shy away from calling it that and discussing climate change in a way that's not sort of confrontational, but just matter again, matter of fact, similar to the way we approach death here. So it's like, this is a reality, this is how we're responding to it, and this is, I mean, the reason we are responding to it is because, again, of this landscape being a resource and sort of a responsibility too.

Matt:

Are there, are there species that are not doing as well for the same reasons? Sort of the flip side of this?

Harry:

We're seeing a lot of, our pin Oaks are really old, so they're suffering, but we also think they require colder winter than we're really having right now. Our European beech are long suffering from a fungal disease called phytophthora and the humidity of our summers, which they don't really like anymore. And that's a tree that's such a central part of this landscape that we're slowly losing, and so what do we do? What we think of the genus fagas, which is the beech genus, and we say, "Well, we don't have that many American beach." In fact, we had one that was felled this summer that definitely predated the cemetery. So we plant more American beach and we try to shore up that genus from being completely obliterated here by occasionally planting younger European beeches, realizing that we're going to have to inoculate them to protect them from this fungal disease, but maybe try to find a tree that can serve an aesthetic, the same aesthetic purpose that the beech did. Although, they're a singular species and the way that they, you know, their design covers all everything below it and their leaves were sort of made to absorb as much light as possible where they overlap.

Joseph:

I feel like Magnolia could replace beech to some degree.

Harry:

I don't think they have the same stature.

Sara:

Yeah. They don't have the elephant form.

Joseph:

Yeah, I see.

Harry:

Nothing can really replace beech and maybe that's the point. In a landscape like this there is some degree of loss.

Sara:

We're always open like all year to the public. I think though, during quarantine, when people were asked to stay put and stay in their homes, anybody who otherwise would've had to take a car or train one of the larger parks, if they're living around here, we are, the second biggest green space in Brooklyn next to Prospect Park. So yeah.

Harry:

I think opening our accessibility during COVID was very much sort of a return to our understanding that this place can serve as many things to many different people at the same time. I mean, as we were dealing with the, you know, unprecedented increase in burials, we were also seeing unprecedented visitorship for people coming from non-burial related, just, leisure activity. So that there was the fact that we were serving where our business is burying the dead, but we also provide this as a green space for the community, for people who want to, who can safely socially distance in a place that doesn't promote active recreation, but one passive recreation. So sort of more thoughtful experiences and, not to sound hokey, but commuting with nature in a space like this. It's not a natural landscape, this is very much a designed landscape with view corridors and, you know, planted atriales and vistas and so on.

It's conceived though, in a way, to allow nature to seem sort of more powerful and larger than you and you to sort of be humbled around it. But that can also aid those who are grieving and can also, you know, add a place of security in a time which was very disruptive and confusing. Yeah. Scary, scary. Yeah. I think that's like you look at this landscape and sort of, there is a calming element to it being here.

I don't think it's hokey to think of the cemetery as a place where you can think about life and death. I think that the whole point of it was conceived that way to have these large living organisms be in a place in which the dead were buried. It's sowing, mean, like not in a subtle way, the continuity of life.

Matt:

I think our relationship with death and our relationship with cemeteries has changed, not necessarily for the the better over the last 150 years, but people used to come and picnic in a cemetery and people used to, like their relationship with death and their dead relatives, they were a lot more intimate with death, I feel like.

Sara:

You know, it's hard to know what the sources of that are, right? Like, I feel like the visible relationship with death and how we're, you know, conceiving it, like people not visiting their lots as frequently or not picnicking, i, I don't know if that is like a direct cultural evolution specific to death, or it's just the fact that people move away from their families. People are spread all around, you know what I mean? And also just as a millennial myself, like preparing for the end and your parents end is really expensive. And so I think, I mean, I know myself and my peers of my age and even younger, a lot of what they're seeking are, you know, more ecological, less expensive alternatives, like green burials, like composting, such and such.

Last spring was so scary. But this spring, I am noticing way more how flowers trap light in a way where I just get, I feel very emotional. So yeah, it's been really, it's been really nice. Everything smells and looks really brilliant.

Harry:

It's true.

Matt:

Yeah. And there is something comforting about the fact that there's a rebirth in spring that we can sort of yeah. Recognize and celebrate. Now, after going through something as dark as COVID was.

Harry:

That's the whole like ying and yang of this place that, you know? Like you come here to visit the dead relative and you see a beautiful Vista and you, you know, there's this terrible year that's full of burials and loneliness, and yet, and in that quiet you kind of evolve or you start a new thing or you appreciate an old thing, or, yeah.

Matt:

Yeah, I think that captures the original intent for why the place existed in the first place, so yeah. Greenwood was built for those kind of experiences.

Thanks for listening to wild talk. This wild talk short was produced and edited by me, Matt Dellinger, with help from Jay Erickson and Emily Kagan Trenchard. Special thanks for this episode to Harry Wild, the director of public programming and special projects at Greenwood Cemetery who helped arrange this. And of course, thanks to Joseph and Sarah. Visit our website wildtalkpodcast.com to see photos, related links and more information about our guests. If you enjoy the podcast, don't forget to rate, review and share with friends. Be well and we'll see you out there.