06 - Apples and Honey: Sweetness in Dark Times

“I need to create a new ritual to help hold and acknowledge this backlog of grief. But I need it to be more than just wise words and deep breathing. I need a ritual with teeth. ”

What can the wild world teach us about how to push through in tough times? And how can we use those lessons to help ourselves, and our kids, look towards a future none of us can yet define? In this short, co-host Emily Kagan-Trenchard goes on a deeply personal journey to craft a new ritual for finding ways to keep going.

Starting from the Jewish tradition of eating apples dipped in honey, Emily explores the strange and beautiful ways that bees and apple orchards survive from generation to generation. Emily calls upon her family, co-host Jay Erickson, Field Maloney of West County Cider and Josh Viertel of Harlem Valley Homestead to talk about the things that help all creatures get by. From snuggle puddles and booze to intergenerational trauma and legacy, we head into the dark places to help bring all of us some sweetness and light.

Transcript

Emily:

So this is 40.

Emily:

And I have the most perfect and beautiful little boat one could want to be on in this storm. It is still a storm. God, and I just wish we were all making it to the harbor right now.

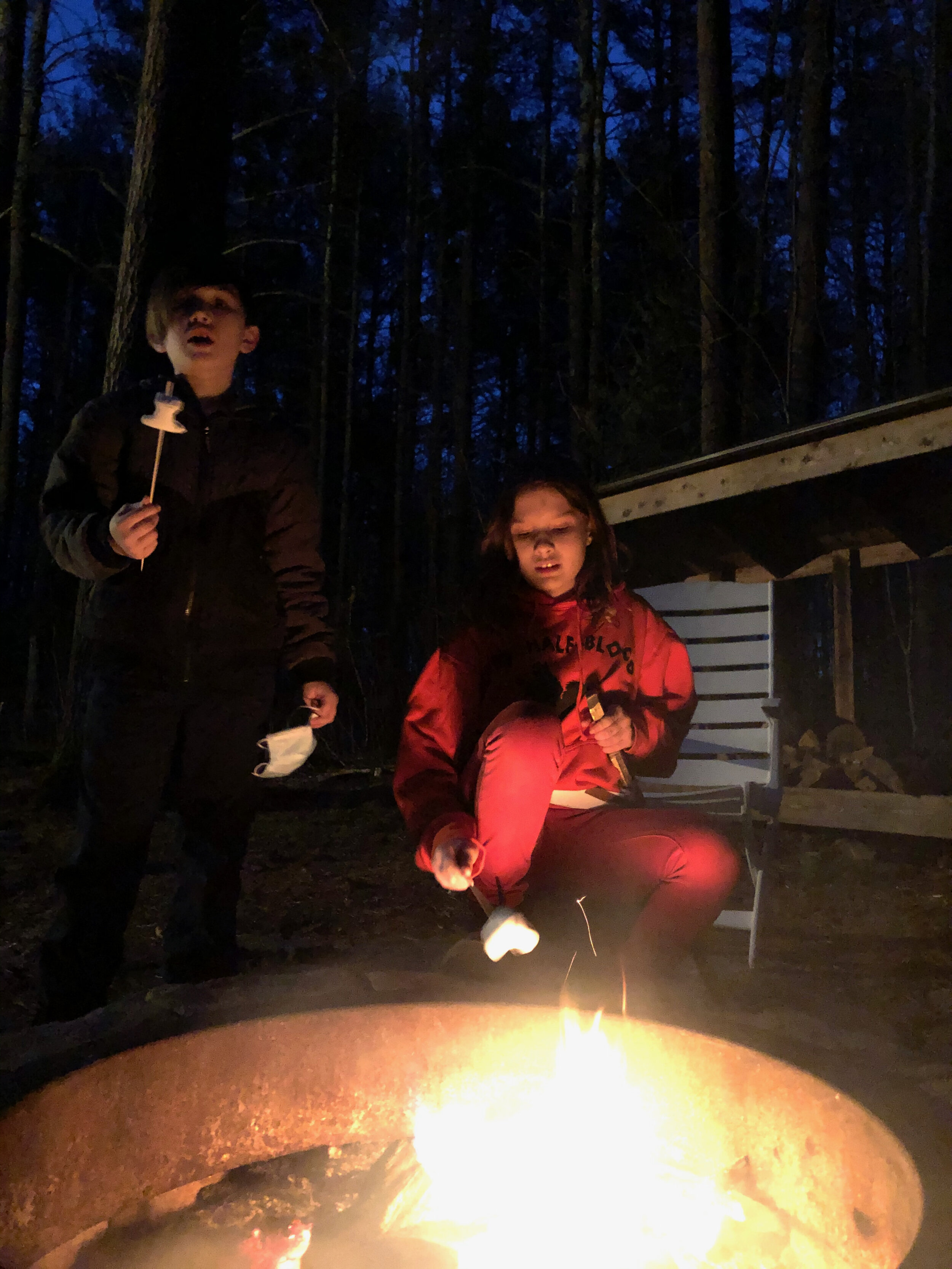

On my 40th birthday this year, I could finally say it out loud. I'm not okay. My life before these empty days feels like it belongs to someone else, and the future is a faith so fragile I can only bring myself to say it's name in a whisper. Getting social engagement only through screens, or faces half-smothered by a mask, has given me a kind of emotional nerve damage. So many of us are at the breaking point, but the hardest part is watching the toll this is taking on my kids.

My son broke down the other day, after one of life's small annoyances pushed him over the edge. He screamed from the depths of his eight-year-old belly and went running into the woods behind our home. When I caught up to him, weeping and collapsed on the ground, and asked him what was wrong. He looked me dead in the eye and said, "I can't live like this. What is even the point of living if it has to be like this?" I managed to scrape him, and the remnants of my own heart, up off the ground and get us both patched back up with some cocoa and a movie. But a few days later, on the eve of her 10th birthday, my daughter lost it as well. The screams that started over some incomplete chores lapsed into sobs of despair so deep. My child disappeared and a young woman took her place.

"No one needs me anymore," she cried, with a clarity that cut me to bone. And I get it. I do, I get it. I've got 40 years of memories to keep me warm and striving, but still this smear of days so scorched by computer screens, so stunted in their potential, and flavorless in their passing feels like a walking death. In 2020, the CDC reported a 25% increase in kids as young as five to 11 years old showing up to emergency rooms suffering from mental health issues like depression and anxiety. The toll this crisis is having on all of us is so palpable but often hard to talk about. Because trauma literally robs us of our ability to make meaning together.

That's part of the definition psychologists use to define traumatic events. When the world as we know it suddenly disappears and we're left wondering who we are and what we're supposed to do now, that stress, that untethering, it can become traumatic. It can leave us feeling exhausted, foggy headed, angry, and hopeless, especially if we don't find ways to make new kinds of meaning for ourselves. So, when yesterday is today, as far as the eye can see, how do we give shape and meaning to the passing of time? How can I help myself and my kids see that was then and this is now, in a way that acknowledges all we've been through and how awful it still is, but opens the door to a future that none of us can yet describe.

Gideon:

These times are hard, really hard, especially for a kid.

Adeline:

Yeah.

Emily:

Yeah.

Gideon:

They expect us to do so much work.

Adeline:

Yeah. This may not be a big portion of somebody else's life, because they've already had a childhood, but it's a big part of our life because all of these experiences that we would normally have just been poofed.

Emily:

I need to create a new ritual to help hold and acknowledge this backlog of grief. But I need it to be more than just wise words and deep breathing. I need a ritual with teeth. Big existential, time-bending problems like this usually call for some wisdom that has stood the test of time. So I started thinking about Jewish rituals and symbols for marking time and acknowledging loss. It's an old joke that we Jews have so many holidays because we have so many reasons to cry. From multicourse meals that re-enact our escape from slavery in Egypt to making triangle-shaped cookies mocking the hats of our enemies. All of our Jewish holiday traditions are loaded with layers of meaning.

There's a Jewish new year's tradition that I kept coming back to, of eating apples we dip in honey to make a wish for sweetness in the year to come. In the depths of this winter, that pithy explanation of sweet wishes suddenly seemed like a false front, a pretty covering for something else within. First off, if this ritual is just about sweetness, do I really need to eat both apples and honey? Isn't that overkill? Why not some other fruit? Why not a feast of cakes and cookies. Second, we take the time to say two different blessings over the apples and honey separately, even though we eat them together.

Emily:

Perfect. And then we say something over the honey-

Family:

I know, I know that seems like a small detail, but Jews do not take dipping foods casually. And when we do, we usually bless the whole thing at once. So two blessings, this was no accident. The Jewish holidays have always been a kind of tether for me and for the kids. A well-worn pattern we can fall into that stitches us to family far away and to generations past. The closer I looked, the more signs I began to see of some secret compartment at the heart of this ritual of dipping apples into honey. But what makes apples and honey such important symbols to reflect on as marks of a year that was and a way to look forward to the year to come?

Emily:

Ready?

Emily:

You want to taste the honey and apple?

Gideon:

Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Emily:

Honey is like liquid summer. Cracking open a jar, my co-host Jay Erickson had given me from the bees of his own hives. The kids and I were transported instantly back to his farm and the lazy day we spent swimming in the pond last July.

Emily:

You can bring the dish closer to you so you don't drip.

Adeline:

This tastes like springtime flowers.

Emily:

Yeah Addy you taste flowers in it?

Adeline:

Mm-hmm(affirmative). I don't know why.

Gideon:

Tastes like poppies I think.

Adeline:

Almost.

Emily:

I think Jay said it was Echinacea, that was the name of the flowers.

Adeline:

They should change the name to Echagoodner because it's hecka good.

Gideon:

I see what you [inaudible 00:08:31] springtime.

Gideon:

You make me a little happier.

Emily:

I asked Jay what the bees were up to right now as the year drew to a close.

Jay:

In the fall. The hive kicks out all the males because they don't need them for the winter. They don't want them for the winter, they just sit around and eat all the honey and they're... And the queen probably has enough sperm to get things going in the spring and they'll be able to raise new males or drones. So get rid of all the dudes, and then they formed this bee-ball where it's all the workers and at the center of the bee-ball is the queen. And this whole entire ball moves through the hive over the course of the winter consuming honey to keep warm and to keep alive that they've stored up over the summer. So that's what they're doing right now. And the amazing thing is that at the center of that, I believe she's the queen is it's like 80 degrees or 90 degrees or something.

It's quite warm at the center of that ball. And it might be eight degrees outside, but they're just burning honey and sort of generating warmth and clustering. And then the workers on the outside kind of lock up. And it's almost as if... When I was, a lot of these protests and stuff and protests, I've been a part of that outer layer, oftentimes people lock arms and there's this sort of group inside. And then when people get fatigued or injured, they sort of swap out. It's basically the same deal they do in this bee-ball where, when they get too cold on the outside, they sort of tag out and girls from the inside go to the outside layer and they just move through the hive. And hopefully depending on the weather and how much honey they have stored they make it through to the spring.

Emily:

The bee-ball, that's what I'm missing. The vibration of the hive to keep me warm. Those others who lock arms with you and tap you out when you're exhausted.

Jay:

But also I just learned about hibernaculums.

Emily:

Leave it to Jay to also point out the creepy, weird version of this metaphor.

Jay:

Which are basically places in rock usually, or little small caves where snakes gather in the winter and they don't fully shut down or having it. They just slow way, way, way, way down. And there can be hibernaculums with garter snakes which are in our area, that have thousands of them. So I had these image of these little pockets around us that are hidden with thousands of snakes just woven together in a hibernaculum.

Josh:

Absolutely, yeah.

Emily:

This is Josh Viertel. Farmer, slow food activist and co-founder of the Harlem Valley Homestead who was walking with Jay, as he told the story of these snakes snuggle parties.

Josh:

Yeah. I mean, that's such a beautiful and sort of almost terrifying, but I think about my own gut response now to closeness in the context of a pandemic.

Jay:

The snakes are not socially distant.

Josh:

They're not socially distancing. But just the thought of being that close to the community has so much draw for me. But then also there's the sort of trauma and the feeling of that's not safe to do anymore. And I feel like I'm really looking forward to sort of healing that wound collectively so I can feel right to be close that way.

Jay:

Right. Yeah.

Emily:

I know exactly what Josh means. To be terrified of this thing we crave the most. We don't know how we're supposed to interact with each other anymore. Even in the small moments of sweetness we find. Like the day the election was finally called, all of Brooklyn seem to be dancing in the street. My husband and I talked that evening about how great that brief moment of connection felt, but how awkward it was for us to figure out how best to join it.

Geoff:

I loved what that woman said to us. It was just kind of like having a dance party on the corner, where she'd say congratulations. I felt... That's the thing. Because I didn't know what to say, we all make awkward eye contact now over our masks and we can't even get a decent facial recognition of are you invited? We just have such a limited facial recognition vocabulary that we're having, just our eyes met her when she said congratulations. I just felt I'm like, "Yes, that is the thing. That is the thing we need to be saying each other."

Emily:

That's what we're saying.

Geoff:

That is what we're saying to each other right now. Congratulations.

Emily:

Congratulations.

My husband and I marked the occasion of that evening by opening a bottle of sparkling hard cider, made from the apples of a hundred year old orchard.

Geoff:

We are good?

Emily:

We are good. Pop it.

Geoff:

Okay.

Emily:

All right. We marked this moment with that same tool of ritual, a drink, old fruit and old troubles both transformed through the alchemy of fermentation. As two native Californians who are now well over a decade into raising our family in the Big Apple. Our relationship to the city felt deeper now.

Geoff:

Having gone through the plague in New York. And that's not to say that it's... Every place has gone through its own plague in its own way. But as an epicenter, as a place that was hit so hard, as a place that is so physically intention with the requirements of life under COVID. It's so hard... Socially isolated in New York.

Emily:

Yeah it's the hive, it literally is, like where we all congregate, where we literally swirl to keep each other warm and sane.

So the honey we dip is also a reminder of the hive. Not just the immediate sweetness of our labor, it's the warmth in the work we do together, and the structures we've built to keep us all safe. But I think we also need some snake energy in this ritual, something to acknowledge how terrifying closeness has become and how we aim for it's still. A way to push past that paralysis and into a hope for... Well a hope for what? As we sipped our Century cider that night in November, I couldn't help but think of the generations of work it took to make the drink that fizzed in our glasses, and what the hell kind of legacy we would be building for our kids that could be equal parts apology, and fresh start at something better.

Field:

I'm Field Maloney. I'm a proprietor of West County Cider, and we make hard cider. We're the longest running cider house in the country. We started in 1984.

Emily:

Field Maloney made the cider my husband and I drank that evening. He knows a thing or two about legacy and about apples.

Field:

I was in fifth grade, my mother and father and I have been making and selling hard cider from local apples in Massachusetts, in Conrail Massachusetts and now in Conrail and Shelburne Massachusetts ever since. I mean, I think my focus in the last five years are cider in terms of cider making has partly been to try to find these old apple orchards that a lot of the growers either the growers have gone out of business and the orchards have been sold and they're either abandoned or plowed over, or the growers are still in business and they're growing apples but they're like that orchard is too old. It's fruit it's not yielding high enough. And I'm like, wait no that fruit is fantastic. That fruit makes the best cider. Can I work with this orchard? And then don't give up on this orchard yet. It's got so much to offer.

Emily:

Field is someone who can see the potential in things others have given up on. In each apple is itself a kind of potential incarnate, not just because the sweet flesh of the apple protects the seeds inside. The thing about apples is that they reproduce kind of like humans. The next generation is never an exact copy of the parent. It's a mix of genes that result in all sorts of variations on the theme. So you can't just keep a bunch of apple seeds around from say a Granny Smith apple, and then plant them expecting to get bright green skins and deliciously tart fruit. No you actually have to cut a branch off a granny Smith tree and then graph that branch onto another apple tree trunk to get more Granny Smiths. That clipping you take is called budwood. And the tree you frankenstein that branch to, is called the rootstock. The rootstocks are apple trees bred to be good hosts for these pieces of budwood. Sturdy and reliable, a good foundation for someone else's future.

Field:

And so actually there are some old farmers around here who just in their sort of farmerly pass times actually does it where he's got an apple tree where he has grafted about eight different varieties of apples onto that apple tree. Because you can just take branches from one budwood, from one variety and graft it onto this apple tree, and then he's taken it from another variety and grafted onto it has all these branches coming out with different apple varieties. So if you were like, "What kind of apple tree is that?" Well you'd have to say, "Well it's a Cortland but it's also a Mac, but it's also a Gala, but it's also a Baldwin, but it's also a Cortland, so-

Emily:

It takes a tradition of farmers passing down clippings from generation to generation to get any particular kind of apple to grow and be around for eating or baking or making cider. In the 1800s there was a vibrant apple growing and cider making culture all over this country. But that wealth of apple knowledge written down in hundreds of books and pamphlets by farmers across the country was almost impossible for people like the Maloney's to use over a century later.

Field:

When my father was getting into cider making in the early years of West County Cider. So in the eighties, when we started making hard cider commercially, most of the books that we look to, there was a vibrant, hard cider making culture in the 1800s. And there were lots of ideas about this apple variety makes a great hard cider, or that apple variety makes a great hard cider. And so my father got these books, these use books from the 1800, there were a few botanists and horticulturalists Liberty Hyde Bailey was one of the great names and shouldn't go entirely forgotten who had these catalogs of all these different apple varieties. And Oh, this makes an incredible cider. The problem was you couldn't find that fruit because it only existed in textbooks. The apple variety had been almost entirely vanished, almost entirely.

It's sort of a variety goes extinct that can happen for apple varieties definitely. But a lot of them had been held, preserved at the Geneva orchard, the core. It's a joint collaboration between the federal government and Cornell university, which has always been a big agricultural school. They have an orchard it's called USDA Germplasm Repository, that's the technical term for it. But it's the largest variety of apple varieties in the Northern hemisphere. So it's basically a library. It's like the famous Alexandria Library of Egypt of apple varieties, or the Library of Congress of apple varieties.

Emily:

This living library grew because people were really into making all kinds of new apple types. Apples for eating, apples for pressing, apple sauce, you name it. But unlike experiments that can be cataloged for future generations in a book, or seeds that can be gathered and slipped carefully into marked envelopes until someone wants to plant them. Each attempt to make an apple that was bigger, or sweeter, or breader or whatever is preserved only in a tree. A tree that must be watered, tended, and grafted onto new rootstock if the original starts to die. A lot of work goes into preserving each and every variety of apple that still exist today.

Field:

So that orchard has a tremendous amount of apple varieties. And my father knew a guy who worked at that orchard and said, "Hey, can I walk through this orchard this spring and gather budwood? So I can plant out my orchard as a test orchard to see different at what of these fabled varieties make great cider?" And we also took two cuttings from this apple variety called the Redfield, which at that point in the late eighties, they were just still keeping it in the orchard because it was such a freak. It's a cross between a red flesh Siberian crab apple that has a red flesh. In other words, it makes a rosé juice. It's across between that and the Wolf River, which is an apple out of the Midwest, but it's known for its big, big ripe fruit and its sweetness.

So it was sort of a classic American apple. And so this is across of that. The Geneva developed in the 1930s, that the Cornell Geneva guys, the federal agricultural research station bread, because they were looking for a way to make applesauce red. And so they bred this apple, which has a bright red flesh, but has big fruit, not small crab apple fruit. And as they're walking through this orchard, the guy was like, "Yeah that makes us incredible red flashed apple. We've never found anything to do with it." Because what happened is they bred it because they were looking for a way to make applesauce red. But by the late thirties, food science technology had gotten sort of so modernized that they developed food colorings to make applesauce reds they no longer needed a red flashed apple. And so the apple was forgotten about and left in an obscure corner of the Geneva orchard basically for 50 years.

And then my father's walking through the orchard in the eighties and they're like, "Oh, this has this really cool red flesh." And he was like, "Well, I'd love to make rosé cider. So why don't I try growing a few of those? And then, so we planted some of those in our test orchard in Conrail Massachusetts, which is where we're about five miles away from right now as we sit. And those Redfield fruit made this sort of striking pink hue juice that made a rosé cider. And we were like, man that is... And not only did it have this vibrant hot pink color, but it had this incredible sort of red fruit like raspberry, strawberry on the palette.

Jay:

I think that's my favorite.

Field:

Yeah. I mean, I think it's sort of one of the ciders that West County is most known for and famed for at this point. So it's been planted across the country now by cider makers, as cider making has taken off. And I would say that my father really... I don't think it would be speaking too strongly to say that he really brought this apple out of obscurity.

Emily:

There's an old Greek proverb that says a society becomes great when old men plant trees whose shade they'll never sit in. When people work on something they will never directly benefit from, when they leave a gift for future generations, we begin to live longer than our own lifetimes. Our sense of time becomes more spacious when our lives start to have meaning on an intergenerational scale. Think of all the things that are holding you up right now, maybe even literally. Every chair or bed, every chain of farmers and grocers linked by roads and bridges, every series of digital handshakes that allow you to give bits of ones and zeros to all the people in that chain in exchange for this sack of apples or bottle of cider. The billions of microorganisms that performed the alchemy of fruit into boozy bubbles.

Apples are a pretty perfect symbol of a gift from unseen hands, a gift we enjoyed a day but requires work to pay it forward to people who may never know our names. That's the funny thing about legacy. It's kind of like trying to be cool. If that's your primary goal, you can never really achieve it. It's not something you can plan out ahead of time. It's something that emerges and take shape as you do the work itself. And sometimes you don't get a choice and how that work's going to go for yourself or for the people you love. When Field's father died unexpectedly, he knew he had some big shoes to fill if he chose to slip them on.

Field:

And now right before he died, the Redfield cider was starting to be really recognized. It was funny. I think he was sort of tickled pink and delighted. He had gotten an email from the Harvard club and he wasn't a Harvard grad, but they were like, "We want to do a talk on cider making. Can you come to New York city?" And he died that... And he sent me an email saying, "Oh, look at the app. The people are getting into even the Harvard club wants to do a talk on cider making." And so he died. So I had to go down and do that talk, but it felt like in some very vivid way I was continuing his. And that winter I remember that was the winter he died. I went out into the orchard because I had been working in the wine trade and Napa in vineyards.

And I went back home and went back to the orchard and he had died, but his footprints it hadn't snowed. So his footprints were still in the orchard because he had started pruning. And so there was something very intense about that. And I guess what I was saying about Redfields is right as he died, he was starting to see that people were asking him for cuttings of Redfields and among the world of cider makers, it's still fairly collegial but if another cider grower says, "Hey, I want to plant, can you give me some scionwood or budwood?" You don't charge them. You give them some cuttings and you'd mail it to them. And so he was starting to mail cuttings of red fields to cider growers in Colorado and Virginia. And now Redfields are being grown by commercial nurseries at much larger scale.

And so the Redfield is growing across the country and I think it would have delighted my father because he definitely played a key role in the funny chain of happenstance that just like the funny role that the plant breeder back in the thirties who knows his name. Who said, "I'm going to finally make this apple sauce. It's going to be... Plant this and this is going to make a red fruit for make apple sauce. And then of course the apple sauce was... They didn't need it anymore because they were using food coloring for their apple sauce, but they didn't rip up and throw away the few plantings, that tree, they were like, "This might be used someday." And then 50 years later, a man in the eighties is walking through the orchard and gathering budwood and gather some from that tree. Because it sounds really cool. And then he plants it and then he passes away, but it's being propagated again and now people are planting it across the country. So it's the circle.

Emily:

What about during this pandemic what's helping you guys get through this?

Gideon:

Well, probably still being able to see friends every once in a while, being able to go outside.

Adeline:

The things that's getting me through is remembering that there's still a world out there that we may be all shut down but there are still people behind the screen. And remembering that there's still a world out there that I can access, that I'm not going to lose all hope and collapse because it's not as open as I want it to be. To push through in order to see people again. And that's really what kind of drives me every day until I take one step at a time and knowing that me learning and learning how to make the future better and staying inside and following safety precautions of wearing a mask, and staying socially distant is going to help us get better. And knowing that my actions are going to help people, it's really good.

Emily:

Here's the ritual I've landed on. Fair warning, this one's got teeth. Light some candles and place them where you'll notice their light and the shadows they cast. Like the snakes, the look we're going for is warm but slightly creepy. Step one, surrender. Wave the white flag and drop all your weapons. Raise your hands slowly and place them one over the other on top of your heart. You are now to become undone. From the most ancient part of your bones and fall into whatever good solid thing is nearest to hold you. Lay the entire harvest of your grief out before you and name each piece.

Step two, take stock. Find some pictures, or play some music, or gather momentos about the time before the pandemic. And then grab some things that remind you of this past year. Some recording of the life that you've lived that you can stare at like a receipt. Proof of these strange days and their kinder siblings. Put these things where you can see them. Next, grab something to drink and a bite of something special. Wine, cider, apples, and honey if you have them. Place these gifts of now next to the receipts of back then so they can all snuggle.

Step three, give thanks. Put some part of yourself flat against the floor and think for a moment about every hand that went into building the surface holding you up in this moment. Think about the people who hammered the wooden boards, or welded the frame of the apartment building. The care they took in cutting the material to the right length, lining them up true. The dust that was swept away, the doors that open to let you in. Think about the architect who planned and the person who made sure the construction would hold up over time. Send out a few clear breaths of gratitude for the work of invisible hands. Literally holding you up in this moment, who never expected anything from you in return.

Step four, leave a mark. Then pick a person you miss and give them a call. Record a video or audio message if he can't get through. But take a breath and be brave even if you're faking it at first. Tell them about the broken parts, about the things you miss, and the things you nearly forgot. Tell them about the gift of food and drink you made for yourself this evening, and how it feels to sit in front of the fire. Tell them about the deepest warm that you can find. And the spookiest shadow. Go slow. Remember to breathe a lot, puff a little more oxygen into the flickering embers at your belly with each thought. Then tell them about the apples, about the borrowed roots that hold them fast. Tell them about the tracks you're leaving in the snow, tell them so that they know you're here humming alongside of them in the dark.

Emily:

Any other thoughts on apples and honey before I wrap here?

Adeline:

Well, they're delicious.

Gideon:

Yeah.

Gideon:

I appreciate the sweetness and the sourness of the new year. And that's all.

Emily:

Anything else?

Adeline:

Eat your vegetables, kids.