03 - War and Trees, with Zainab Salbi

“To really heal between the gender divide, or between the racial divides... we need to articulate what’s the path to reconciliation. We need to have the other side show up remorsefully and sincerely, from their heart. A heart can hear another heart.”

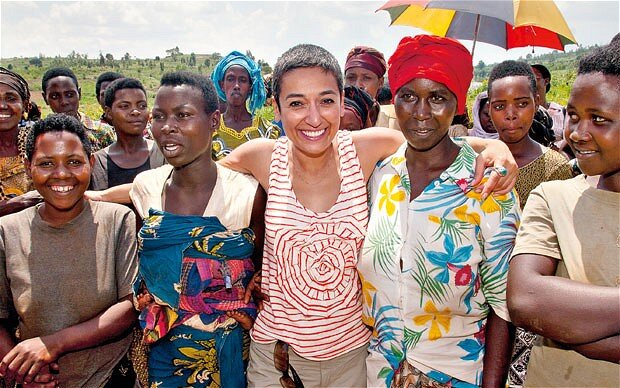

Humanitarian, activist, writer and TV host Zainab Salbi has become a leading voice for women’s rights. A survivor of struggles both geopolitical and personal, Zainab has taken her hard-won insights about conflict and healing, and used that empathy to organize and inspire. Along the way, she’s developed a deep connection to the natural world, where she finds rich metaphors that inform her work.

Zainab grew up in Iraq, in the shadow of Saddam Hussein’s regime, before fleeing to the United States at the age of 19. In 1993, she founded Women for Women, a global humanitarian effort that has helped half a million women affected by conflict. Her awards and accolades include inclusion in Foreign Policy Magazine's “100 Leading Global Thinkers” and People Magazine's “25 Women Changing The World.” She is the author of several books, including her most recent, Freedom Is An Inside Job: Owning Our Darkness and Our Light to Heal Ourselves and the World.

We met Zainab for a crisp, socially-distanced, leaf-crunching walk at a nature preserve in Pawling, New York, 75 miles north of New York City. It was November, 2020, just days after the Presidential election, and though the votes were still being counted, it was already clear that America remained divided.

Impressed by her experience working with survivors of global conflicts, we wanted to ask Zainab about what comes next. In the wake of #metoo and #blacklivesmatter, and as we confront the growing of violent extremism in the US… Now what? How can societies and souls overcome our greatest failings?

Being in the woods with Zainab seemed to bring out every bit of her passionate wisdom. There was no time for small talk.... We dove right in.

Transcript

Jay:

I had just shared a Rumi quote, "Look at the birds making great circles in the sky. They fall and it is in falling that they get their wings."

Zainab:

Oh, that's so true. It's so true. It's been my life story.

Jay:

Jumping off the cliff.

Zainab:

I've jumped a couple of times now, sometimes by force, sometimes I jumped willingly. But the one time I jumped willingly, it felt like you do stay in the safety of the land, but with the anxiety and the fear it brings to you, or do you jump and take a leap of faith into the unknown? I always say ... I give speeches about that, right? You'll be shocked, sometimes you land on water. Sometimes you get your wings, but you always land. Where do you want to take the risk? Do you die out of your own fear or do you take a leap of faith, and trust that you can at least on your journey?

All:

Welcome to Wild Talk.

Emily:

Let's head outside.

Jay:

Hi, friends. Thanks for joining us for wild talk, the show about people who work and think in uncharted territory. I'm Jay Erickson.

Emily:

I'm Emily Kagan-Trenchard.

Jay:

Humanitarian, activist, writer and TV host Zainab Salbi has become a leading voice for women's rights. A survivor of struggles both geopolitical and personal, Zainab has taken her hard won insights about conflict and healing, and used that empathy to organize and inspire. Along the way she's developed a deep connection to the natural world, where she finds rich metaphors that inform her work.

Emily:

Zainab grew up in Iraq in the shadow of Saddam Hussein's regime, before fleeing to the United States at the age of 19. In 1993, she founded Women for Women, a global humanitarian effort that has helped half a million women affected by conflict. Her awards and accolades include being named one of Foreign Policy Magazine's 100 leading global thinkers, and People Magazine's 25 women changing the world. She is the author of several books, including her most recent Freedom Is an Inside Job, Owning Our Darkness and Our Light to Heal Ourselves and The World.

Jay:

We met Zainab for a crisp, socially distanced, leaf crunching walk at a nature preserve in my hometown of Pauling, New York, 75 miles north of New York City. It was November, just days after the presidential election. It was already clear that whatever the final results, America was still divided.

Emily:

Impressed by her experience working with survivors of global conflicts, we wanted to ask Zainab about what comes next in the wake of Me Too, and Black Lives Matter, and as we're confronting the growing threat of violent extremism in the United States, now what? How can societies and souls overcome our greatest failings?

Jay:

Being in the woods with Zainab seemed to bring out every bit of your passionate wisdom. There was no time for small talk. We dove right in.

Zainab:

Here we are, it's my daily ritual.

Jay:

You do it in the morning usually?

Zainab:

Either in the morning or in the summer, I was doing it also in the evening so on the one end of the day. The experience I have with nature is an emotional one for me, because I grew up in the city and very disconnected from nature. Even though I grew up overseas in Baghdad, Iraq, we have nature, we had gardens and all of that, but when I came to America 30 years ago, I was like, "Birds, yeah, whatever." It was like whatever. Then I started being introduced to nature and the turning point well for me was, a retreat I did in North Canada with indigenous people there, where they put me out on the land for four days.

Zainab:

It was a leadership retreat, actually, and part of it was to be put out on the land with nothing.

Jay:

By yourself?

Zainab:

Yeah. Sleeping Bag. But you're not supposed to take book, pen, paper.

Emily:

Oh, wow.

Zainab:

Your exercise is that you have to stay present to nature. You're not supposed to write, read, do anything, like you and you. I just would lay down and I'd do all kinds of things with nature and I would lay down. That was my first time ... It was a transformative moment, because I feel, I heard Earth's heartbeat. I was just like, laid down on the ground, and it's just like, I never heard this before. That was a transformative moment. It created a new connection for me. Fast forward, the last year I nearly died.

Zainab:

Literally, it was a very extreme case of Lyme disease and a viral infection that took me to the ICU for a week. There was a moment in which I could not breathe, and I thought I was going to die. I breathe with a lot of interventions and doctors and machines and all of that. But it took me a very long time afterwards, to be able to breathe actually normally, and to walk and to eat normally. It took me months and months and months and months of trying to even just get my energy back to just to be human back, and nature saved me. I am not joking. I'm not even saying it's ... It saved me.

Zainab:

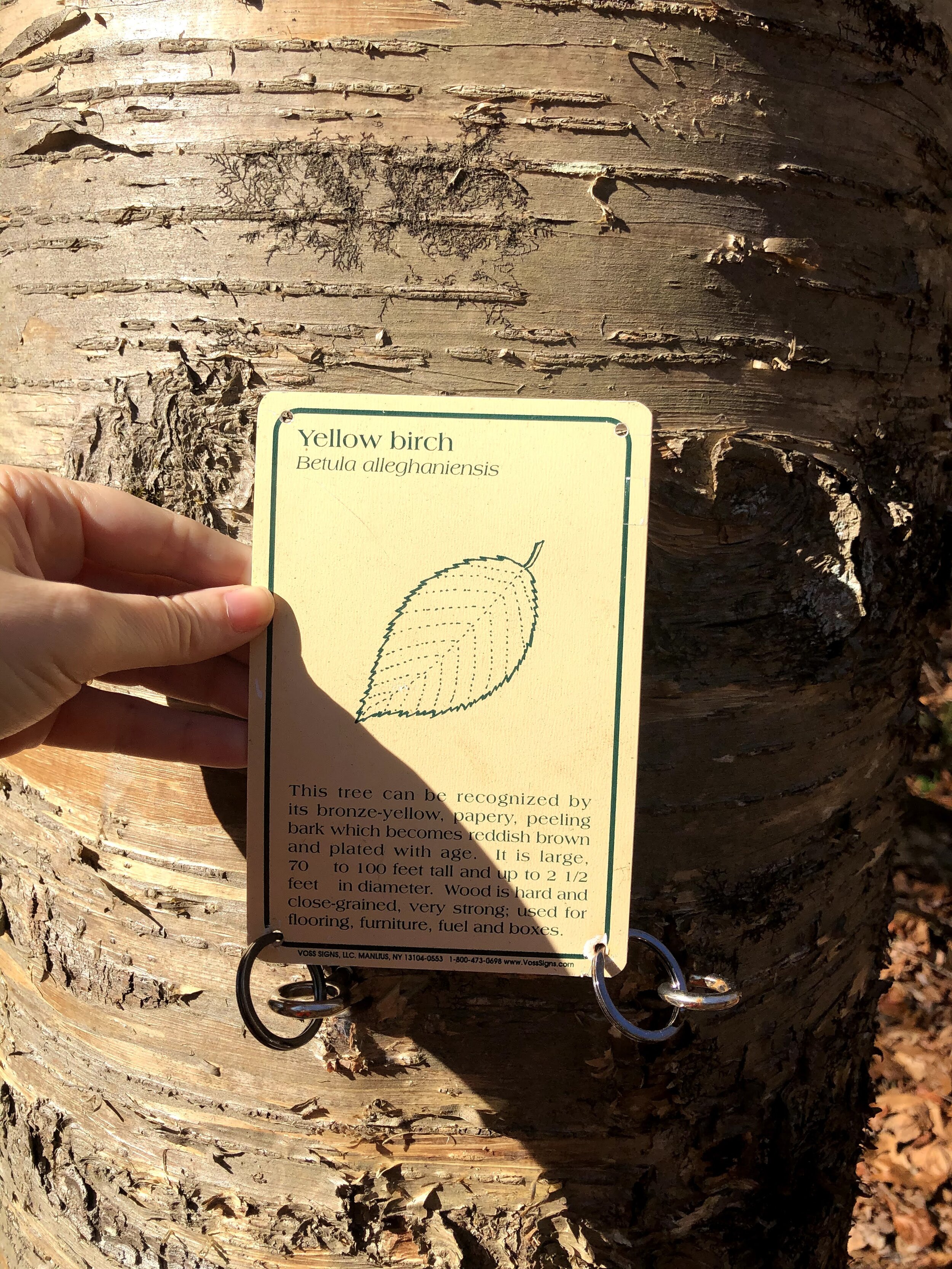

I moved out of the city and I would walk ... I did not have the energy to walk just the stamina. I walked by the beach, and I felt every wave was just giving me a force. It was like giving me, it's telling me "Go, keep going," and I would walk. I was like trying to train myself to walk again. Then each wave became my support system, like, "Go, keep going." Then the trees I start walking every day also by ... I moved to another place where trees ... Each tree I would hold it. I feel like I was getting like the ... Trees support each other in their roots.

Zainab:

They feed even the weak. They don't abandon the weak. They actually, it's in their best interest to keep the even the weakest tree alive.

Jay:

Even across species.

Zainab:

Across ... right. I would hold it and just so I can get energy so I can walk just to breathe again. I just feel like nature was my, what do you call it? Fans. Not fans, what do you call the support people?

Emily:

Cheerleaders.

Zainab:

Cheerleaders.

Jay:

Cheerleaders.

Zainab:

You can go, you can keep going. I have since, it's my friend and it gave me a life again. I thank it. Here when I come ... It's a long answer to your question.

Jay:

It's beautiful.

Zainab:

I have different conversations. Sometimes it's like, this is a tree I love.

Jay:

Oh, hello.

Zainab:

Sometimes and this is a fun project to me, I just like pick a tree with a big ... I just put my back on it just like, we often are hunched back and we go moving and I just allow myself to be held by it. I can even feel the difference right now. It's just like, "I got you." I believe as we transform and we go into our lives, we need the energy, the person, anything that I got you, believe that I got you here and I feel like when I do that, this tree reminds me, "I got you."

Jay:

That's so powerful.

Emily:

I also love how intimate that relationship seems to have become for you. Sometimes people think nature is this big vastness, but to you it really truly sounds like a friendship-

Zainab:

Oh, my gosh.

Emily:

... on a very most personal level.

Zainab:

Yes, yes. When I was still building my energy, I was staying at a home… ... in a friend's home and there was peonies in the spring. I was just emerging, I was getting better every day. But thanks to nature, basically and there were these peonies and the peonies open up very slowly. I felt my life ... We went on the yellow trail I suppose.

Emily:

Yes.

Zainab:

That's the red trail.

Emily:

Shall we go back?

Jay:

Yeah.

Zainab:

Sorry, I've been ...

Jay:

The peonies.

Zainab:

The peonies, so I would meditate every day by the peonies, and I was just like ... They blossom so slowly. I felt my life was connected to them as they were opening up, and as they open up, I was opening up. Yes, it's very personal. It's personal for me, because when we separate ourselves from it, whether it is with each other or whether with us and nature, when we separate ourselves from it, we dehumanize the other. I'm not sure if that's the right word. But objectify the other, then we don't acknowledge their soul or their heart.

Zainab:

For me part of solving the issues with nature and climate change and all of that is to personalize it, and to learn from it. Actually, it's a great teacher. It's just a great teacher. I feel the only difference between us and trees, us and animals, they just move in a different rhythm. But it's their behavior patterns of tree, of a mother tree with her child tree is actually so similar to us. I have a teacher who used to say, "We human move so fast, that we stopped listening to the wisdom of nature. All what we need to do is move in the spirit of nature, which is slow to medium."

Zainab:

When we move slow to medium, we actually are able to hear it and understand its wisdom better. I think that's what COVID period did. It forced us to go slow to medium and that's the connection that we're all talking about with nature, right? All it takes is slowing down to understand the intelligence that is all around us. When we disconnect and think that we are superior than the others, then we lose out. It's same thing with Women for Women.

Zainab:

In the case of being a victim of war you [inaudible 00:12:43] her by saying, "She's a victim, I'm not." she's in this culture. I am not. This was before the Me Too movement was created some sort of solidarity with women. But frankly, up until then, it was very frustrating talking about the realities of women in other cultures to American woman, because they kept on seeing it as a cultural issue. These are other women.

Emily:

That's happening over there.

Zainab:

It's happening over there and one of the things that I love the most about Me Too movement is American woman spoke up and not only American woman, it's the peak of America, Hollywood celebrities. It's like, "Oh, we are also abused." It's like, "Finally, you tell the truth." All this time we cover it and we say, "Oh, it's these Congolese woman, and it's Afghan woman, and is Bosnian woman and all of these women, the other women." Now they go through extreme, horrible things. But sexism is sexism. In one culture, it expresses itself in an extreme way. In another culture it expresses itself in a subtle way. But it's still sexism.

Emily:

Right.

Zainab:

For me, since I launched Women for Women in 1993, the simplest act was to write a check, because it's accessible. But what I wanted is to see her and for her to see you, because in our stories, as humans we are equal. In our monetary realities, we are not. In our technologies we are not, but a heart is a heart, wherever you are and we are equal. The sorrow, the pain, the joy, the love, we all understand these feelings. That was a mandatory is, write to her, share your stories.

Emily:

To her, individual.

Zainab:

Right.

Emily:

Yeah.

Zainab:

That became that transformative experience is the writing for both sides. Because for the woman who is receiving, for the victim side to simplify the word, she was being seen, and that was giving her an emotional support that I am not alone. The world has not forgotten about me.

Emily:

Yeah, there is this person named Samantha, who lives at this address who sees me?

Zainab:

Absolutely. For Samantha, you'd be shocked how the American woman or we had also women from 68 countries was being impacted. I remember one story of a wealthy woman, husband works in Wall Street. She had been communicating with her, what we call sister in Rwanda. Over time, she even went to visit her in person. Then Lehman Brothers happened, the crash of the financial market happen, and they lose everything, they lose a lot.

Zainab:

She calls me and she said, "Had I not been in communication with that woman, with my sister and had I not visited her in her home, and understood her story, not only of loss, but of rebuilding, I would not have handled the crash, and the loss of material things I encountered in my life in the same way.

Emily:

Wow.

Zainab:

I would have been devastated. But now I look at it and I smile and I was like, "Wow, okay, we can do it."

Emily:

That's incredible.

Jay:

That was very much this feedback loop of helping the women who have experienced trauma through war, they're helping with their emotional resilience, which in turn feeds resilience and emotional awareness. It's like a mycelial network-

Zainab:

Completely.

Jay:

... of the trees.

Zainab:

Just like with nature, if we nurture nature, nature will nurture us. It's exactly the same fashion.

Emily:

Mutual aid.

Zainab:

It's totally mutual. Now, I find it fascinating. The world talks about the accomplishment like, she raised $120 million sort of big deal in the women's movement, because women's groups don't go above a certain budget, so we'll get marginalized funding. It was a big story, but not one of these acknowledgments talk about the letters and the personal connections. They talk about the money raised. That was the measurement of success.

Emily:

Put it in terms of letters, what was that success in terms of letters for you?

Zainab:

Millions, millions of letters and pictures. In the early days, I used to process the letters myself. These were the good old days when you're involved in everything at a startup [crosstalk 00:18:15].

Jay:

Startup.

Emily:

Startup mode.

Jay:

Startup mode yeah.

Zainab:

Then the more you grow, the more you get taken away from what you're most passionate about. But anyway, it was an American woman who wrote letters about her garden. She described the garden in details and the evolution of the garden. It was very personal for her and the woman she wrote it to was going through war in a besieged city in Sarajevo. They were shelled as they would line up for water and food and bread and all of these things. The Bosnian woman was vicariously living through the garden and like this hope, there is somewhere else there are flowers blossoming and then does-

Jay:

Peonies opening.

Zainab:

The peonies opening, exactly. Exactly.

Emily:

I always think about that power of storytelling when people say, "Well, what good are English language arts degrees and so forth?" It's almost like this pandemic, anytime we are alone and don't have that connection to the world, suddenly the currency of those arts, those letters, those stories, that ability to share is like, "Oh, now it's sort of laid bare, now we get it."

Zainab:

It's true. Every time we tell our story, I feel the story becomes the gift to the other. When I hear someone's story, I feel it's their gift for me, it's the most honorable gift from me. Okay.

Jay:

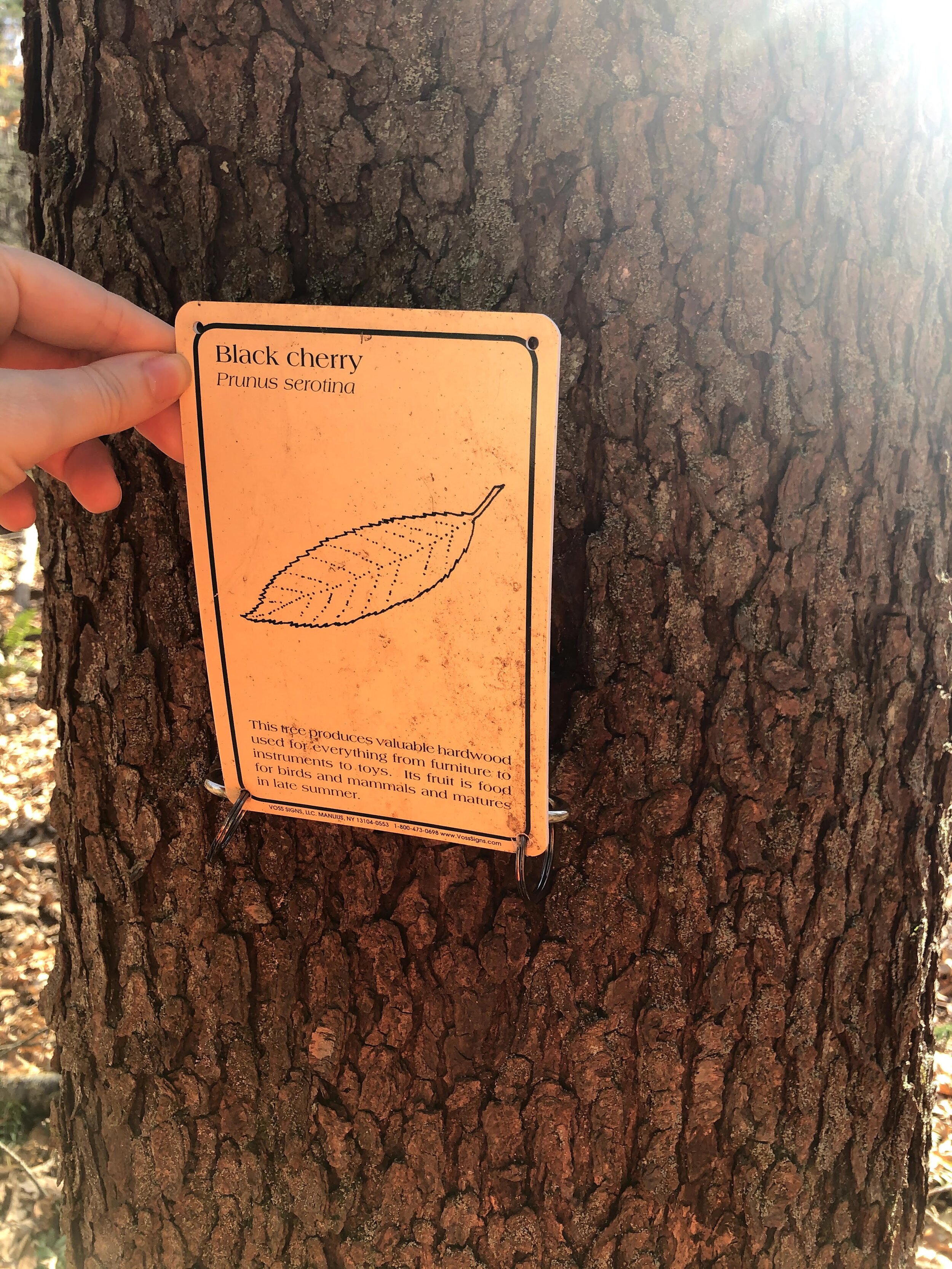

But these oak leaves are notoriously slippery.

Emily:

Yes and crunchy.

Jay:

And crunchy.

Emily:

I was glad to hear you start to draw this connection to the Me Too movement and the shared sisterhood. But I'm wondering if you could talk a little bit about what that bond and connection of sisterhood is, out beyond just being on the losing end of patriarchy. What is it?

Zainab:

Very, I love this, because I love this. If anything, I'm obsessed about this subject, because I think there is an evolution, right? The first breaking out of the cycle of oppression is to speak the truth, is to break away from the silence. As women, silence was the code we were given, you have to stay silent, right? The first wave is to break out of the silence and speak the truth. That is a very scary, very scary proposition.

Emily:

To step off the cliff.

Zainab:

When I broke my silence, it was jumping off the cliff. I had true, real fear in me, a fear of life and death when I broke my silence. That was a real thing. But that's the first step. Then the second step, you sort of ... I'm telling you my personal journey at least. You first like, "Wow, when I break out of my silence there's power in it," because it's like you own the story. You're afraid, you're afraid, you're afraid and then finally you say, "I am going to speak up," and the speaking out, you're stripping naked in front of the whole world. But you are taking control and doing it.

Emily:

You're the one disrobing?

Zainab:

You are the one and so no one can blackmail you with that fear.

Emily:

Right, the worst that could possibly happen is to be stripped bare and you've done it to yourself.

Zainab:

You're like, "This is how I feel.

Emily:

On your turf.

Zainab:

My time. Here I am. My Word. My miracle.

Emily:

Your language.

Zainab:

My language." I define the story of my story. It's very powerful, right? Then it's preceded by anger or fierceness, maybe not anger. Fierceness like ...

Emily:

Like an embodied anger?

Zainab:

It's a positive anger. I really have no problems with anger. It's a fierceness like, charging. Because you understand how much has been inside and the release outside. The cry first, but then you have like, "I want to help others to do it." There's an energy.

Emily:

The drive to put that anger to productive use.

Zainab:

To productive use just a Joan of Arc kind of –

Emily:

Like a mission.

Zainab:

... mission. But then it's one thing that we speak up. It's important, and we show the fierceness. How do we now lead like women, not lead like men? How do we define and how do we find our feminine voice and our feminine power? We have so much suppressed and narrowed the feminine as being kind and nurturing and beautiful, and all of that very much on the surface, and I think is defined by the patriarchy itself. To be a feminine person is to be soft and nurturing, kind, as opposed of us defining the feminine and us finding it within us, and the depths of it and discovering all of it in us.

Zainab:

Now, the journey is to show and demonstrate what leadership means in a new way. Not to repeat the same patriarchal way of leadership, so that you have to go inward and find the connection inside, find your own voice not in reaction, but in pro action.

Emily:

In definition of the actions you do, not the actions that you're no longer doing.

Zainab:

Exactly, and demonstrating and that's my call for all women right now. That we are ... So far we're doing good, but if we don't take the moment to define our own feminine values and demonstrate how we lead from our strength not in reactions, then we may lose.

Emily:

Are their feminine values that aren't at the individual level? Is there something that could be said of feminine values in that's more ... I think I struggle with this because the gender binaries, my partner actually recently came out as non binary. I've been struggling a lot with, "Well, what is the gender binary? Where do they help? When I'm in nature, I see binaries, I see binaries and they're useful. They're tools that help us show a duality and the importance of attention to duality-

Zainab:

1000% yes.

Emily:

... and yet at the same time, some of the binaries that have been operative in our lives are just so toxic, and we got to get rid of them.

Zainab:

Absolutely.

Emily:

What are you still seeing, the positive in this feminine binary, particularly in leadership?

Zainab:

Well, I feel we need to discover it in ourselves first. I don't think of feminine as soft, I think of feminine as fierce.

Emily:

Sure.

Zainab:

But there is a different energy than the masculine. I'm not against the masculine, but I'm against the patriarchy.

Emily:

sure.

Zainab:

It's a different concept right?

Emily:

Yes.

Zainab:

Few feminine values that I have come to discover from really talking to other women who have done their journeys, and courageously so, you have to go inward. One of them is the creation of safe space. Safe space is where we can have uncomfortable conversations. This is what we need in our country right now.

Emily:

So much so.

Zainab:

A lot of people say, "Well, what do you mean by safe space? We don't know how to enter into a safe space." That's a feminine value, how do you create safety? Feminine values, how to generously listen to the others. Whether you agree or you disagree with them, but really understand how to completely listen to their story as they experience it and see it. You don't have to agree. But you need to see it from their perspective.

Emily:

Just hold the space for the story.

Zainab:

Because it's a growing process for you.

Emily:

To listen

Zainab:

To listen. There's listening, where you're asking questions from your mind, that comes out as interrogating. There's listening, where you're listening from your heart, and you're inquiring from your heart. People understand ... There is a tone difference. There is a difference. That connection to your heart is a feminine value, which by the way can happen in men too. Feminine is not women.

Emily:

Right. It's more an aspect. It's not what's in your pants or ... yeah.

Zainab:

But it's a new skill set I believe we need to ... a new emotional skills that we all need to teach ourselves, women and men in order to emerge out of this in unity with ourselves, with each other and frankly with nature.

Emily:

Yeah.

Jay:

It sounds like creating that safe space is less about this tired idea of the feminine is like soft, and like let's throw out a bunch of beanbags for people to go into its more about this strong, grounded, courageousness of the heart, and I think there's this opportunity to reclaim the word courage and merge it with heart, because in French [inaudible 00:28:18], it's like the same word means heart, and it's like you have to have heart. It's all really coming from the same place. I think we've lost that idea that courage can be heart centered, and you can be courageous in your listening, in your empathy and to inhabit somebody else's heart.

Zainab:

Actually it takes the heart of courage to listen with your heart. The easier courage is to go and fight a battle. It's physical, it is aggressive.

Jay:

Right it's authoring, the battle piece.

Zainab:

It's authoring right? And we have all mastered that. I mastered it. I'm sure a lot of people who have mastered it in their own lives. We know how to do that, but the patriarchy has taught us the aggression, fight for your rights. The different courage to show up in integrity and in alignment between your voice and your actions, and an alignment between your values and who you are. That's just the very ... and to speak your heart. I feel like the emotions we need of the moment, essentially the language is no longer intellect. The language we really need to develop is more feelings.

Emily:

I think of the, if you think of the bower, like the stand of trees that protects what's in it, that safe space is created, not because something is soft or gushy in between there. That space is created because of trees buffeting from the wind. Literally it requires strength to have a safe space within.

Jay:

But they have to be rooted and they have to be connected to each other.

Zainab:

Exactly.

Emily:

Right. It's a shared effort to provide a strength that allows for the shelter.

Zainab:

Exactly.

Emily:

How do we get there?

Zainab:

Well, that's why I feel this a ... I mean, COVID may have been a blessing in disguise, because ... I don't know about you, but you know the weeks that everyone in earth slowed down and we all went to our hearts mostly, and politicians were speaking of kindness and empathy and compassion. I'll say it in another way. I'm from Iraq. I went to Mosul when ISIS ... three weeks after ISIS was overthrown.

Emily:

Oh, wow.

Zainab:

The ISIS story was particularly personal for me, because it's my people.

Emily:

It's not abstract. This is ...

Zainab:

It's like, how could the people in the country I grew up in and the language I spoke, the religion I grew up in, how could they actually do this? It was horrifying. It was an absolute heartbreak. I was curious to understand. I went to Mosul and I literally walked the streets and people started walking towards me, garbage collectors, teachers, housewives.

Emily:

Everyday folks.

Zainab:

They all were saying the exact same thing. They were like, "We became the nuclear bomb on ourselves. It wasn't thrown at ... on us from above, we became the nuclear bomb." They say, "Every time someone came and promised us money and power in exchange for certain actions, we did it." They go back to Saddam's time and they say, "Saddam say do this and we did it. Then Al Qaeda came and they said, do this, and we did it." At first, kill the enemy, then kill the people in the other religions, then kill the women. Then ISIS was where the sons were pointing the guns on their parents.

Emily:

Oh, my God.

Zainab:

They were saying, "We became the nuclear bomb," and they're saying ... There's one woman. She's like tears crying. She's like, I will clear the rubble from in front of my house. I will do it. I don't need help in rebuilding the bricks and mortars. We just need help in understanding how to build a new human being with a new value system, because the old values have failed us. In a way, this was three years ago. But I think the old values are failing us here too.

Emily:

I was going to say, as you were describing that I was thinking about people who speak your language, who are your neighbors, I just watched 68 million of my fellow countrymen-

Zainab:

I understand.

Emily:

... double down and I am feeling that kind of “I don't understand” moment.

Zainab:

And for the same promise of power and wealth.

Emily:

With the same promise, exactly.

Jay:

Well, I think this is the invitation. There's a great moment of political tension. I'm going to quote you, only when I began to see the other within myself, because I truly see the other in them in the quote rednecks of America quote, Arabs of France, quote fundamentalists of Islam and in all of us. From there, we start to bridge the divide between us, between them and many others out there in our inner other, who we live with every day. A true hero is an ordinary person could hold the sword of truth and tell the truth of herself in her good, her bad and her ugly qualities.

Jay:

She makes her choices from this understanding. As heroes we move forward, not in fear and anger and integrity, love and vision. We work from the strength of our spines, rather than the breathless of our chests if we have the courage. Is that how we begin to build a new human being is to own our own darkness?

Zainab:

Well, first of all like that's such a good ... I was like I ...

Jay:

Who wrote that?

Zainab:

I was like it's so true to me, oh my god. I'm glad I still believe the same way. Well, when we look at the other in us, we develop through compassion, and the other in us, the part of us that is ashamed of our actions. We usually do, put it on the side.

Emily:

Moving on.

Zainab:

Move on. I had to learn the hard way to look into it. It happened because I actually am talking about the country, right? In my case, it happened because someone I loved betrayed me. I couldn't understand how could this person do that? I just couldn't understand it. A friend of mine said, "Can you look at the part of you that has betrayed you." That's a hard question. Of course, there is a part of me that betrays me. There is a part of all of us that betrays us, however way, to each has her or his story, right?

Zainab:

But whether it's our shame? Whether it is our malice, our greed, our anger, or just whatever it is that the emotions we don't want to acknowledge. When I looked at these emotions in me, I actually had compassion towards it. I felt bad for it.

Emily:

Your own insecurity?

Zainab:

Yes. Like, rather than being harsh on it, I felt really bad for it like, "Oh, it's just an insecure child here." I learned to actually hold it and accept it. Now, by doing that, it was an automatic understanding of this other person who hurt me, and not only with him with politics and let me explain.

Emily:

Yeah, say more.

Zainab:

I'm a Muslim woman. I am from Iraq. I have color. I shave my head. I can't tell you how much humiliating, insulting, disrespectful thing you go through, even by some friends who make comments about your culture or you and then of course by the public. For the longest time my people were seen as the terrorists, as the crazies, as the warmongers, as the killers. At the beginning, it used to make me very angry. I was just like, would shout at the person who would ... I realized in my anger, I was scaring them and all what they say, "Look how angry you are," and then I get ashamed of my anger, my shadow, and then I shut down.

Zainab:

Then when I started seeing my shadow in me, I changed my tactics. I used to snap out and it's like, "You're racist." The minute I do that, I just see the person, their wall comes in the sense and there's no conversation. I decided to change tactics, and the tactics was only... I could only learn it after I learned to see what Jay just wrote, to see the other in me. Then my tactic now is like, you're afraid and immediately, because they are afraid, the other is afraid. I was like, immediately, there is an acknowledgement. You're afraid that my people will do this, this, like this and there's like, "Yes, I am afraid."

Emily:

Right. It did negate your ... You didn't stop being angry or frustrated but you just change the tactic by which you approached the person.

Zainab:

I changed the tactic. Actually I also moved from anger because my goal is like, I'm closing the roads with anger, so I have to change and find another way, so what's the other way? My goal is to move forward, to not be objectified or cornered into one identity.

Emily:

But also not to say that that's okay.

Zainab:

Absolutely not.

Emily:

Not to back away from not calling it out.

Zainab:

But the only way to move forward is for them to understand my story, my narrative, my identity. What's the point of calling someone a racist if they don't understand why I call them a racist and my own humanity.

Emily:

Sure. I think some people would say, though, is that your job? The burdens back on you.

Zainab:

You know what? It is, and it's unfair. It's very unfair, but in my experience, working in warzones, that the burden is on the victim side. Actually not only the burden, the legitimacy comes from the victim side to show the path forward. You can't let the aggressor define the path forward, because the aggressor ... I'm simplifying that obviously. The bad people, good people, whatever you say.

Emily:

Sure.

Zainab:

The aggressor cannot define the rules of the game, of the new game of “how do you heal.”

Jay:

I remember reading in Freedom Is an Inside Job, which is a great title, by the way for a book-

Zainab:

Thank you.

Jay:

... about the Rwandan process, that the jails and the court system was so overwhelmed, that they resorted to this more ancient form of adjudication and healing, where the elders would get together in front of the village, everybody would witness and the perpetrator would come and say what they had done and speak about their feelings of it. Then they would mete out a punishment, but it was seen not as punitive, more than just aimed at healing. I would call it a healing prescription, where someone who burned down someone's farm to say, "Okay, it looks like you're really atoning for this. You're going to go work on that farm until it's green again.

Zainab:

They did it not only for morally reason. They actually did it for practical reason. They did not have enough jails to put all the criminals in it. They did not have enough lawyers or judges to prosecute all the criminal. Now, look at us in this country, here in America. We talked about the Me too movement, we don't have enough jails for all the men who have violated women. We think it's the Harvey's. It is Harvey Weinstein's and all this is true. But for every Harvey there's a thousand other men who have violated, they just happen not to be famous and rich, right?

Emily:

Exactly.

Zainab:

We don't have enough jails. We don't have enough of a system to deal with that. Same thing with racism, we don't have enough. You find another path, because the path forward ... We all need the path forward both sides, basically including the victim side. I know a lot of people saying, "You know what, forget it. We're moving in our own path." See, I love this tree. It's so cool, because it's like, do you go through that tunnel? Or do you go around it every day? It's a game I play with myself, what do you do?

Emily:

Yeah, I've been struck by these restorative justice movements that really sort of, almost beautiful local character they then take on, because it requires community to come in and do that accountability, right? Because it's not just meeting out a decision once, it's over time, keep that person keep coming to work that field until it was green. That's not any one individual. That is a community-

Zainab:

Precisely

Emily:

... making that repair.

Zainab:

Precisely, and it's defined by the victim, because the victim needs to feel the remorse, needs to feel the sincerity. You get a lawyer writing an apology letter doesn't do it. You get financial, you get money. That helps, but it doesn't heal. To really heal between the gender divide or between the racial divides or whatever, we need to feel. There is a process I believe. We need to A: have the safe spaces, i.e. communities. We need to articulate what's the path to reconciliation. We need to have the other side show up remorsefully and sincerely from the heart. A heart can hear another heart.

Jay:

Let me ask ... Well, I'm going to drop another of your beautifully written quotes. But you write much of world's history rests on hurt and betrayal that have not been truly forgiven. Resentments are carried through generations, families, cities, countries, and peoples all carry unforgiving divides. It takes the same emotional muscle for us to forgive someone who has betrayed our trust, as it does for a nation to forgive another nation, or for women to forgive man. It takes the same courage to ask to be forgiven, as it does to acknowledge our role in whatever larger stories have divided us for centuries.

Jay:

I recently read a piece, just simply bluntly put it, America was founded on two ... has two foundational sins. One being the genocide of the Native American people and two being slavery. We have not reckoned with that as far as I can tell in any meaningful way. How do we begin that process and how do we respond to ... I have had conversations with people who say, "Look, I'm white, I get maybe, some people I was connected to a long time ago did a thing, but I didn't do a thing and I'm not responsible for fixing it." How do we practically move forward in this country?

Zainab:

But the responsibility it comes from the collective. In South Africa, a lot of whites said that, right? Says, "I didn't do anything. My grandparents or whatever did something." The responsibility comes out of the collective privilege. Two humans, one happens to be black or Native American and one happens to be white in the same land. They have two different trajectory in this country. The good white person came out of the privilege, the injustice created. How do you deal with it?

Zainab:

It's not about ... I wouldn't want someone to fluctuate themselves like, "Okay." You don't need to do that, right. But we do need to have a system corrections. How do we go about correction of systems to right the wrong? Some of that is changing our economic system. Some of it is changing our emotional system. But we do need to change system and that is doable. That is possible for all of us to be part of recreating a new way of being.

Jay:

Well, what practically ... I mean I get that and that resonates, but practically, what would a truth and reconciliation process at a national level look like?

Zainab:

It's a good question. I can tell you in other countries how they worked. Right now is the oppress, screaming at the oppressor. Again, I'm using simple language. You did this to me and the oppressor, of course not all the same people. They're good people, they're bad people ... all of that. Some people say, "Okay, what can I do?" Then some people get defensive and try to vote for someone horrible. It's like, "I'm scared, you're going to attack me." I would say, it's a different energy. It's a proactive process, like, "I am hurt.

Zainab:

You did this. I need you to show up and acknowledge, acknowledge, just acknowledge." That's the first step. That creates a union in the national narrative of the injustice. That's what we don't have the same narrative in here. I have a friend who lives in Tennessee, and the caregiver for her mom, elderly mom was doing the icing of the cake for her child, the Confederate flag. My friend was shocked just like, "How could you do that? Do you understand that this is horrible to do that?" She's like, "Why, it's our flag?"

Zainab:

She's like, "No, it's associated with slavery. You cannot." She's like, "No, it's not associated with slavery. It's our flag." My friend's like, "No, it hurts people when you put that flag out. That's why people are so angry and upset because it's hurtful." A simple woman, and I believe, she's not evil this woman, right? She's like this friend, she's so loving for her mother, elderly mother, she's cared ..." We have to believe also, in the goodness of others. We cannot demonize. This is what I don't like about what's happening right now, is we're demonizing black, white people are all evil.

Zainab:

That's not true. How do you distinguish between ... How do you see the hearts of people? That woman was a simple woman, a good woman, who did not have the same national narrative that a Confederate flag is associated with slavery. I think this is part of what's happening in America. We need to create a nationalist, redraft the story in a new way, where we reach to the other and say, "No, this flag means this and that's why it hurts, and that's why people are putting it down and upset about it." Did you see what I mean?

Zainab:

It's creating that Native Americans when I first came to this country I read, bury my heart at wounded knees, right? I was just crying and sobbing and all of that. I had a colleague I worked with I was like, "This is a brilliant book. Oh, my God, I can't believe ..." She's like, "Well, for us, they're the ones who killed us." I was shocked, was like, "What?" I was shocked. There's no one narrative in this country. In most countries, the first process for reconciliation is a public process, where everyone is processing that pain, and everyone has to have the discipline of not projecting anger on the other and owning their story with courage.

Jay:

Right, it starts with truth. You have to have truth before reconciling.

Zainab:

Absolutely.

Emily:

Even a simple statement like “Black Lives Matter,” that's why sometimes it feels like a radical act to just say that because if Black Lives Matter, there's all these things you then have to reconcile with to make that true, in every way that everyone shows up.

Zainab:

But the showing up is not only from all the Trump supporters. The showing up is from everyone equally-

Emily:

Absolutely.

Zainab:

... equally.

Emily:

What book would you say is speaking to you at this moment, right now?

Zainab:

At this moment it's a book that I just finished reading by [inaudible 00:50:34], a Japanese writer. It's about an artist, who suddenly his wife left him and he got lost in life. He just took the car and start driving and driving without any aim, and found a new way of living for him in a cabin up in the mountains, and let himself be lost for a while. Literally, that's the book I just finished. Let himself be lost for a while, and did not paint anymore, and just read and all of that and follow the sound of mysteries, and all kinds of adventures came to him from the mystical world.

Zainab:

Then when he stopped painting, he allowed himself to paint not in the structure that he used to paint, but in a new structure and unbelievable art came out of it. That fascinated, it's almost scared him beauty of the art that came out of it. Anyway, he came a full circle, and he drives back to his wife to integrate and he starts a new life. There's something about that story ...always write in a very mystical ways. There's something about the being ... Because when I got sick, I got lost as well.

Zainab:

I got sick on a peak of my mountain. I was just having show that everyone was talking about, in the news da, da, da all of these things. I was like, doing this and listen advising here and going this. Like top of the mountain, right? The day I was in the hospital, I was getting ready ... I had a booked speech at 5:00 PM, a birthday party for a friend at 8:00 PM and midnight plane to a week in Greece with my friends, and I fall from that to the ambulance room to the ICU struggling for my life. For the year that followed, I was like, "Who am I?" If I can't think and I couldn't think, I could paint, I could do color.

Zainab:

I started playing the piano again. This is one of the thing people don't know about me. I re-taught myself the piano after 30 years of not playing. I start because I couldn't have words. I'm a writer, so it shocked me when I couldn't have words. I was scared.

Emily:

Yeah.

Zainab:

I lost myself, like, "Who am I?" I learned that in that space, this is why I feel everyone has to do their inner journey, because you're going to have to confront your conversation with your heart on your deathbed. If you don't do it, now you're going to confront it, because with all family and friends and loved ones around you, you're still left in that space alone between you and your heart.

Zainab:

I had to confront it. I ended up living between the land of the living and the land of the dead for a year. Here's what I discovered about it, it's actually beautiful. That land of the in between spaces is actually really beautiful. It's harder to be back on Earth, because you have to deal with people and you have to deal with all kinds of shit. But then I learned at one point, I just didn't know what to do. You have no tools. You really didn't have to. I didn't have to. I just learned to trust and I decided to trust life.

Zainab:

Because I was either going to destroy myself and worry or to trust life. Here I am strong physically and I walk and I ... I'm playing the piano and I'm painting, I'm writing again and I'm doing all kinds of things. Coming out of it is like trusting in life works even though ...

Jay:

But you have to let go.

Zainab:

You have to let go and you have to also enjoy your fear. Yes, at one point I was walking in nature and I felt like I was holding the tree and refusing to let go of that identity. "I am the tree. No, no, no, I'm not leaving, I'm not leaving," and literally I like taped it. I was like, I had to realize, surrender to the not knowing and trust life. It's worth it. The journey, the inner journey is worth it. The trust is worth it. The letting go is worth it too.

Zainab:

Here we are.

Jay:

Yeah, thank you for doing this with us

Emily:

There and back again.

Zainab:

Not at all.

Jay:

Beautiful conversation, beautiful day, beautiful walk. Thank you. Thank you.

Zainab:

Not at all. Thank you.

Emily:

Thanks for listening to the Wild Talk Podcast, where we speak with leaders, thinkers, researchers, writers, artists and organizers in natural settings, about their work and what they can teach us about venturing into the unknown. This episode of Wild Talk was produced and edited by Matt Dellinger and Jay Erickson. For photos, links and more about our guests, visit our website at wildtalkpodcast.com.

Jay:

If you enjoy the podcast, don't forget to rate, review and share with friends. Looking forward to next time. See you out there.